Fossil finds ancient termite mating behavior

Women in Agriculture program brings Temple Grandin

Potential for drone spraying in agricultural fields

the season 2024 volume 1

Alumnus shares vision for local agritourism destination

-

Tandem TErmites

Fossil finding shows termite mating behavior existed 38 million years ago -

Decompose

Belk brings fresh expertise to field of decay -

Addressing an issue

Graduate student finds passion for food science, Listeria prevention -

A Focus on Food

Herron brings poultry science background to supply chain research -

Growing Inspiration

Alumnus King Braswell shares vision for local agritourism destination -

The Perfect Recipe

Extension, College and Experiment Station -

Up close & Somewhat Personal

An informal Q&A with Morgan Martin -

Many Missions

Women in Agriculture program brings Temple Grandin -

The Ant Expert

Penick served as a scientific advisor for Planet Earth III episode -

Efficient Applications

Potential seen for drone-spraying in agricultural fields -

Season to Taste

Morgan Adams’ Tried-and-True Strawberry shortcake

-

executive Editor

Josh Woods

-

Managing Editor

Kristen Bowman

-

CONTRIBUTING Writers

Rachel Damiani

Taylor Edwards

Paul Hollis

Mike Jernigan

Katie Nichols -

Layout & Design

Jess Ramspeck Douglas

-

Photographers

Morgan Adams

Molly Bartels

Jonah Enfinger -

Dean

Paul Patterson

-

Auburn University College of Agriculture

Office of Agricultural Communications and Marketing

3 Comer Hall

Auburn, AL 36849-5401

334-844-5887

theseason@auburn.edu

agriculture.auburn.edu

Auburn University is an equal opportunity educational institution/employer. -

© 2024 Auburn University College of Agriculture

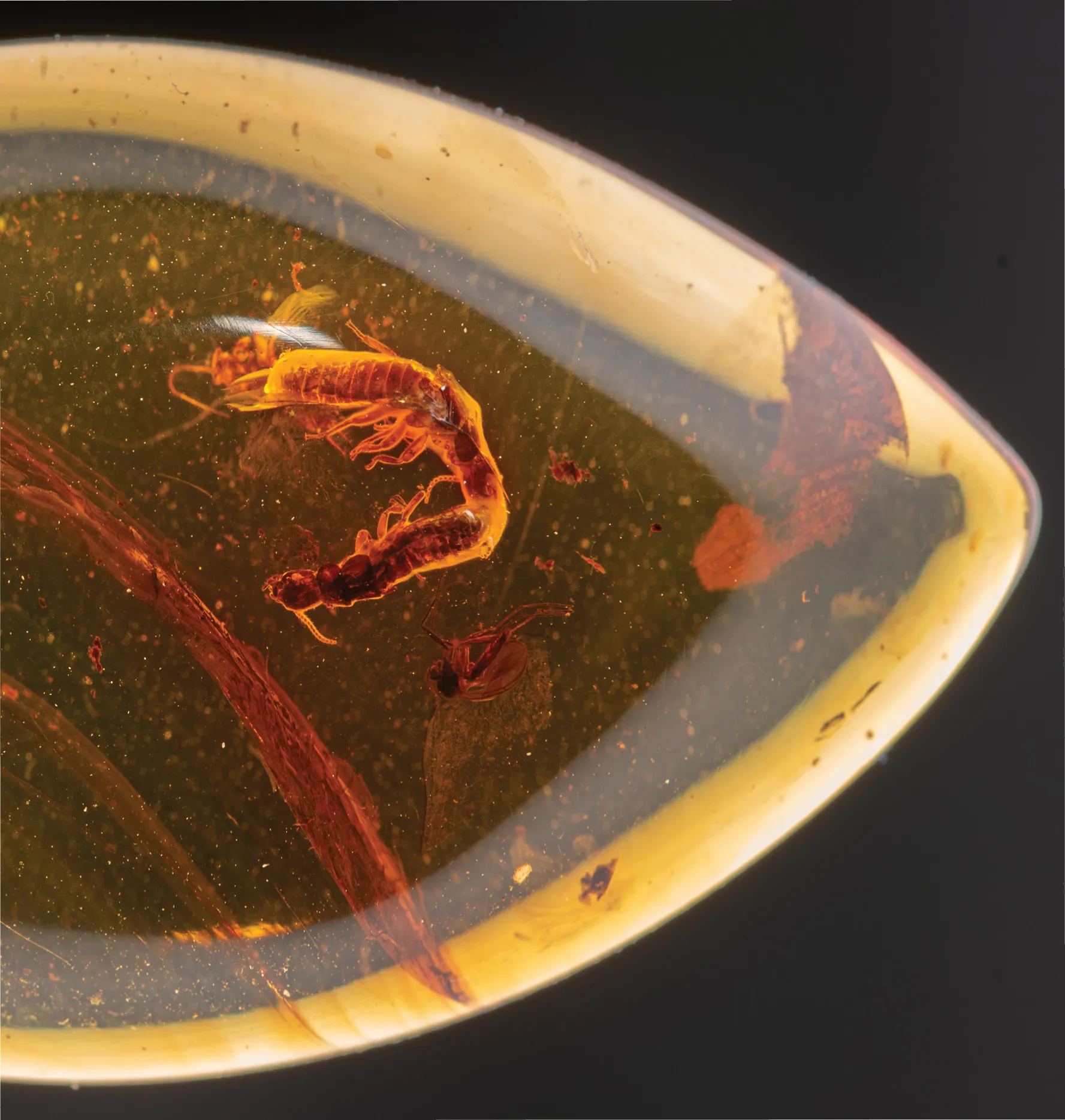

Tandem Termites

Or something like it: Mated to another, together you seek a new nest site by performing an innate mating ritual. You grasp onto the abdomen of your mate, frequently touching his legs with your antennae as you explore new territory.

But suddenly, your mate stops. Struggles. You don’t know why, and you refuse to let go. So — still grasping his abdomen — you attempt to circle him, curving your body closer to his.

And then the reason he stopped is clear. His six legs are coated in sticky resin from the tree you were climbing. Now, yours are, too. Driven by pheromones, you won’t let go, holding on as you attempt to circle the other way until you’re both covered in resin, you’re both stuck, and soon, you’re both dead.

In 38 million years, you and your mate will still be encased in that resin — now fossilized amber — and for sale in an e-shop for fossil collectors.

A unique amber fossil containing two such termites was purchased by Ales Bucek, head of the Laboratory of Insect Symbiosis at the Czech Academy of Sciences, and shared with Nobuaki Mizumoto, then at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and today an assistant professor in the College of Agriculture at Auburn University.

“Termite fossils are very common, but this piece was unique because it contains a pair,” Bucek said. “I have seen hundreds of fossils with termites enclosed, but never a pair.”

The fossil is the only known example of a pair of now-extinct Electrotermes affinis termites, and the findings from this particular fossil were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a leading, peer-reviewed scientific journal.

“Amber provides one of the most detailed and vivid records of extinct life,” Mizumoto said. “However, the process of fossilization may distort the true picture of past organisms and bias evidence.”

– Ales Bucek

In this case, the termites — one male and one female — in the Baltic amber inclusion show a head-to-abdomen contact that resembles the courtship behavior of termites today called the “tandem run.” During this mating behavior, the insects display coordinated movements to stay together while exploring a new nest site.

However, one of the extinct termites is turned parallel to its partner — a variable from how this behavior is seen today.

Mizumoto and his colleagues had a theory about why the positioning was different, so they simulated the fossilization process in the lab.

“Our approach focused on how fossils are created and how behavior changes during the insect’s death,” Mizumoto said. “We simulated the first stage of amber formation by exposing living termite tandems to sticky surfaces. We found that the posture of the fossilized pair matches trapped tandems and differs from untrapped tandems.”

The experiment showed that even if the leading termite got trapped on a sticky surface, the follower would not abandon its partner but try to walk around them — resulting in a position very similar to the pair immortalized in amber.

“Thus, the fossilized pair likely is a tandem running pair,” Mizumoto said. “This is the first direct evidence of the mating behavior of extinct termites.”

It started with her dissertation on ideal environments for human decomposition at Colorado State University.

She then briefly considered a career in forensics before returning to her roots in agriculture.

Belk is an assistant professor in the Department of Animal Sciences and a researcher in the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station, bringing a vast portfolio of meat science and microbiology experience.

She was hired in August of 2022, and is already a favorite among animal science students.

“Dr. Belk and I immediately hit it off during our very first meeting,” said Abby Krikorian, an animal science graduate student. “She really is a one-of-a-kind person who never gives up and always perseveres. Dr. Belk is such a great mentor to me. It’s so hard to put into words all the things she has done for me while on the journey to my master’s degree.”

Microbiomes are communities of microorganisms that cause disease or fermentation. Belk was studying the microbiomes that surround human decomposition for forensic science applications.

“Our question was basically whether you can determine the time of death from the microbial signature on the remains at the time of discovery,” she said. “During decomposition, the microbial communities shift in predictable patterns, which we call microbial succession.”

For example, initially the microbiome contains mostly aerobic (using oxygen), skin and soil microbes, but gasses build up in the gut and cause rupture, which allows the anaerobic gut microbes to join the party. Then, the microbial numbers get so high that competition takes over, then nematodes show up to eat the abundant bacteria, and the factors showing the passage of time continue.

“We wanted to learn whether this pattern is the same in all people, all places, throughout the year, and whether we could truly predict it,” she said. “We worked with forensic research facilities where people can will their bodies. They placed the remains outside, unclothed, and helped us collect daily samples from several points for about a month.”

They sequenced the DNA from these samples and used machine learning algorithms to see if they could tell the time of death from the microbes present.

– Aeriel Belk

Belk never shied away from the stereotypical uncomfortable things, seeing them instead as opportunities for learning and growth.

“I really love bats,” she said as an example. “I used to volunteer for a bat rescue and happily would again if I could find one. I currently content myself with just looking at them in the evenings.”

Meat science is a family interest. Her father is a professor in meat science, exposing her to the field early, even before she truly understood what it was.

She started learning by age 10, when she competed on the 4-H meat judging team. She continued meat judging as she earned her Bachelor of Applied Science in animal science at Colorado State. That degree opened her eyes to the meat industry in America.

“I started to realize how much of a family the group of people that worked in the field were,” she said. “Everyone knows everyone and is excited to see each other and keep up. I also discovered by working in our meat safety lab as an undergraduate researcher how much I loved microbiology, so it worked well when I was able to find a master’s program that would let me do everything I was interested in – meat science, judging, microbiology, safety and teaching.”

She was finally drawn to Auburn by that same combination of factors that drew her to the field in the first place: meat science, microbiology and teaching.

“This job — All I ever wanted was a professor position where I could do my research and teach at the same time,” she said.

Addressing an Issue

atherine Sierra, an Auburn University master’s student in food science, has won multiple awards that hinge on her public speaking ability, including a third-place award for her poster presentation at the 2023 Student Research Symposium.

These are impressive awards for any scientist in training, but even more of a feat considering Sierra became fluent in English only two years ago after moving to Auburn from Honduras for an internship in the Sensory Science and Consumer Research program.

When trying to learn a new language, many people might watch popular television shows or read fiction. But Sierra had a strategy only a scientist would devise.

“I read peer-reviewed papers,” she said.

When Sierra encountered the inevitable difficulty that comes with acquiring scientific terminology in a new language, she reached out to one her mentors, Amit Morey, associate professor in the Department of Poultry Science, for encouragement.

“Dr. Morey helped me and said, ‘You are a good student. You will learn. You are smart and you will learn,’” Sierra said.

Learning English was just the start of Sierra’s journey at Auburn.

After completing her internship, she joined Morey’s research group and began her graduate studies, and she has soared. Sierra received the prestigious National Protein and Food Distributors Association Foundation Scholarship and is chipping away at her research focused on developing innovative technologies to improve food safety.

Morey describes Sierra — and many of his mentees — as “out-of-the-box thinkers” who have the potential to make a positive change in the field.

“She is doing cutting-edge research that’s going to impact food safety and quality,” he said.

rowing up, Sierra said she never would have predicted she would become a scientist. It wasn’t until she enrolled in food science classes at Zamorano University while pursuing her bachelor’s degree that she realized science could help explain questions she pondered about the world around her.

“Every day, I cook all of these things, but I don’t know the chemistry and the science behind it,” she said.

Through her coursework, Sierra gained the tools to translate the food world’s jargon, from dissecting the backs of food labels to gaining fun facts. For example, she was thrilled to discover that part of the egg turns white because of how the protein reacts to heat.

“My brain was exploding,” she said with a laugh.

Committed to pursuing her passion for food science for her career, Sierra’s next step was an internship. She perused a list of universities, and Auburn caught her eye. “I saw Auburn is one of the best universities in the U.S., and it had a top program in poultry,” she said.

Sierra jumped at the opportunity to apply. Once accepted, she began researching a variety of food products, including sugar replacements in ice cream, with Sungeun Cho, assistant professor in the Department of Poultry Science.

At around the same time, Morey noticed Sierra’s affinity for science and encouraged her — both as a young scientist and a person.

“I understand what it means to be an international student, what it means to learn a new language and adapt to a new system of communication,” said Morey, an Auburn College of Agriculture alumnus. “Being patient with these students is the key to helping them grow.”

orey and Sierra are currently investigating how to reduce a disease-causing bacterium, Listeria monocytogenes, which is associated with ready-to-eat meats. It is an important scientific pursuit because infections caused by Listeria monocytogenes, known as Listeria, can be fatal. People who are immunocompromised, older or pregnant are especially susceptible, Sierra said.

Listeria monocytogenes can live on a variety of surfaces in processing plants and then contaminate the food. To help address this issue, Morey and Sierra are conducting research with the goal of removing these bacteria from common surfaces.

Current industry approaches to eliminate Listeria monocytogenes from common surfaces include thorough cleaning and sanitation with chemicals — which can be costly and less sustainable, Morey said. Sierra is part of two studies within Morey’s lab that are looking at alternative tactics.

They are investigating a plasma-based strategy that could be more sustainable than existing approaches. While “plasma” may sound complex, Sierra shares its simple definition, showcasing her science communication strength.

But this sometimes-forgotten state of matter is an important one; plasma has the potential to reduce Listeria monocytogenes that can live on food processing surfaces and even on ready-to-eat food products.

In a nutshell, when power is applied to everyday gases, scientists can create plasma. This plasma contains charged atoms, known as free radicals, that are ready to react.

“These atoms can penetrate the cell wall of the bacteria, in this case Listeria, and can damage its DNA,” she said. It can also kill the bacteria.

For future studies, they are investigating whether this plasma-based technology is effective over the long term and its effects on how the bacterium functions. The scientists are currently conducting additional experiments in preparation for publishing this work.

Meanwhile, Sierra is working to complete her master’s thesis about using a biodegradable film made from chicken gelatin to wrap cooked chicken with the goal of preventing Listeria monocytogenes.

While working on her degree, Sierra said there are sometimes long weekends and nights, but that being a part of Morey’s tight-knit team keeps her motivated. She said Auburn is exactly where she wants to be while growing into her own as a scientist.

Through her graduate program in agriculture, she has had the opportunity to travel to conferences, engage in top-notch research and receive impactful mentorship.

“These are opportunities I never imagined I’d have,” she said.

What’s next for Sierra? She hopes to pursue her doctorate. Morey is right in her corner, and he has confidence she has the foundation to succeed at Auburn and beyond.

“She’s very focused, a great problem-solver, forward thinker and highly disciplined,” he said. “These are great characteristics that a future scientist or industry professional should have, and these will help her excel anywhere she goes.”

A Focus on Food

A focus on food supply chains is a fitting academic pursuit for Herron who experienced food insecurity at points in his life.

“There was a time period where I was really poor and kind of struggling to make it,” Herron said. “I really like the idea of working with humanitarian supply chains.”

Herron isn’t alone. Experts estimate that approximately one-third of college students and 34 million people across the U.S. do not have reliable access to enough food for their basic needs.

Shashank Rao, who is the Jim W. Thompson Professor in the Department of Supply Chain Management, said supply chain research, which is the study of the behind-the-scenes process for getting an item from one point to another, can provide key insights to help with this food crisis.

“There’s plenty of work out there that’ll tell you that growing enough food to support a population isn’t the issue,” he said. “It’s really getting that food to where it needs to be, distribution, logistics — these are the biggest challenges.”

One example of a clog in the food supply chain process: ugly produce. These imperfectly shaped fruits and veggies — perhaps an oblong bell pepper or a curvy carrot — are perfectly tasty and nutritious. But, this produce are often wasted due to its appearance, Rao said.

– Brock Herron

For Herron’s master’s thesis, he focused on a different aspect of the food supply chain in Amit Morey’s lab in the Department of Poultry Science: how to reduce food waste and loss, while promoting food safety.

“There’s lots of hungry people,” said Herron. “If there’s some way to minimize food waste that’s also more sustainable and better for the environment and can prevent healthy nutritious food from getting thrown away, perhaps there’s another better way of doing this.”

Herron investigated the general practice grocery stores use, known as first-in, first-out — meaning that food unloaded from trucks first should be the first to be placed on the shelves.

“This operates using the logic that product that arrives first will expire first,” Herron said. “What we were focusing on was if that logic is actually the best way of doing things.”

He specifically examined poultry that is transported on trucks that were not at full capacity, known as less-than-truckload (LTL). In these LTL scenarios, poultry is often subjected to heat as the truck makes its stops.

“Every time you open the door, the cold air comes out and the heat comes in,” he said.

Herron hypothesized that this exposure to heat could expedite poultry’s expiration, and he built models to test it.

“What we found was that product that was subjected to more temperature abuse during the delivery route before reaching the grocery store would expire before product that was not temperature abused,” he said.

Herron went on to present his impactful research at 10 conferences, and he won the Graduate Student Award of Excellence from the International Production and Processing Expo.

“Due to his outstanding research, Brock has a fan following at conferences where people looked forward to visiting his poster to find out more about his work every year,” Morey said.

Beyond his professional success in the College of Agriculture, Herron said that he found a pivotal mentor in Morey who he describes as a father figure.

“I didn’t really have anybody else at the time to talk to if personal things happened, so I would go to him in his office,” Herron said. “He would calm me down and then help me pick up the pieces and start again.”

One day, Herron hopes he can provide the same type of empathy and listening ear for his own students. After earning his doctorate, he plans to become a professor in supply chain management.

When asked about what he would want to give to his future students, Herron said, “I would make it known that they could always talk to me about anything because that is what I needed.”

Until then, Herron is putting in the hours in the College of Business — teaching Management of Business Practices to undergraduates, enrolling in his own coursework and preparing to fine-tune his area of focus. Both Rao and Morey describe Herron as humble and a hard worker.

“Brock has been through a lot to get here, and so that really tells you that he has the kind of gumption and staying power that very few students of his age have,” Rao said. “He has the level of maturity that you typically would not expect people to have at this stage in their career.”

Herron’s life may have had as many twists and challenges as the supply chains he studies, but he said he’s glad to be in the driver’s seat now.

“I’ve always been searching for something that I could choose for myself and was not dictated based on my life’s circumstances,” Herron said. “The doctoral program was finally an opportunity where I had the freedom to choose to do something because I wanted to, not simply for survival.”

Growing Inspiration

chocolate lab follows his owner down a stone path lined with glossy green plants, perfectly aged terracotta pots and delicate tables.

A woman named Morgan holds her 5-week-old son while she lunches with a friend, Emily. Morgan is here for the plants — “the only place I buy them,” she says — while Emily is here for the impeccably inspired interior and exterior design. Both ladies smile at the passing lab, who is unfazed by the smell of their pastries or the gentle squeaks of the stretching baby.

This utopian paradise is Botanic, of course, and Tucker the lab is as at home here as owner and Auburn University College of Agriculture alumnus King Braswell.

Botanic is an exceptional display of agritourism the likes of which one might expect to experience in Northern California rather than just off Highway 280 near Tiger Town in Opelika. It includes an elaborate garden center and retail shop as well as two dining options — The Market and The Grille — all housed on the former grounds of longtime Opelika eatery Cock of the Walk.

“There is a tremendous amount of history on this property,” Braswell said. “The pond is more than 100 years old. We hear stories all the time from guests who rode horses here, who fished here, who knew the owners before Cock of the Walk.”

“We were going to head down 280 and look for property out there,” Braswell said. “And I said, ‘honey, let’s just go up to the old Cock of the Walk and see what’s up there now.’ We pull up, and doggone, it’s for sale.”

Nestled in a sort of basin, you feel removed from town the second you drive onto the Botanic campus. To the left are the Greenhouse and Garden Center, and to the right is the pond, while straight ahead is a massive, eye-catching structure that constitutes much of Botanic. Inside this reclaimed-brick-and-cedar-shake structure is a stunning interior patio, a martini bar, a beer garden, a wine cellar, and a truly unique private dining room inside a stone grain silo that Braswell brought over from Dawson, Georgia.

It’s a place designed for gathering, and Braswell says that people — and plants — are at the heart of Botanic’s purpose.

raswell earned his Bachelor of Science in horticulture with an emphasis in nursery crop production at Auburn. He started working for himself in plant production right out of college.

“I quickly realized the production side of things satisfied the scientific side of my brain, the manufacturing side of my brain, but it didn’t fully satisfy my craving for everything horticulture,” he said.

Braswell had a passion for the artistic side, as well, for where horticulture meets people, feeds them and inspires them.

In 1993, he opened Blooming Colors, a garden center that operated in Auburn for 23 years. The business offered him the opportunity to serve others in a way he hadn’t before. Not only did it provide a retail service, but the nursery offered at-home gardening and landscaping services, as well.

“I always say, every person’s home is a castle,” he said. “Everyone should feel special in their own home and have that sense of satisfaction coming home every day. And it meant a lot to be able to help them feel that.”

The business grew, and he added Crepe Myrtle Café next door to the nursery. But it had its limitations, including, simply, the size and scope of the property.

There are plans for a 10,000-square-foot hydroponic vegetable production facility, cottages across the pond with edible gardens for staying guests, and crop production such that Botanic can become a campus that truly consumes what it grows.

“We’re still in the starting stages of what Botanic is going to become,” he said.

His goal is a destination that showcases urban agriculture demonstrated in a real and impactful way, while building a reputation that allows Botanic to be a national brand and horticultural leader.

They’re getting started in this with Botanic-branded products for sale in the market, including jellies, jams, pickles and preserves all handmade by Executive Chef James Jolly, who Braswell said brings a high level of culinary excellence to Botanic and shares the vision for what the brand can become.

“We’re fortunate to have an amazing team who are embracing and sharing this vision — what is now kind of a cliché term — for a farm-to-table culinary experience,” Braswell said.

Jolly has worked at Botanic since June 2022 and said it means a lot to be part of the team.

“It means a lot to me, being from the area,” said Jolly, a native of Smiths Station. “There is nothing quite like Botanic in the Southeast that I have seen. To have the opportunity to work here as the executive chef is nothing short of a blessing.”

“I love to make them, I love to see people buying them, but I hate to see empty shelves,” he said with a laugh. “Keeping shelves stocked is the hardest part, and coming up with new things is the fun part.”

Jolly and his team have a schedule for the provisions based on what is in season. It is the best way to create a cost-effective product but also the best-quality product, he said.

“Come summer, for example, we know strawberries are going to be in season, so we’ll make our strawberry preserves,” he said. “We’re using produce when it is at its peak.”

t the foundation of Braswell’s goals is a deep-rooted desire to inspire others, and the next step in doing so is through gardening symposiums in 2024. These have been a goal since Botanic opened, but he wanted to get the business up and running first.

“It’s important to me to have the respect and legitimacy to teach people about it,” Braswell said. “I need to be able to do first, then tell.”

“This team,” he said. “And their passion for the customers and the community we aim to serve. I’m passionate about them, and I’m really passionate about everything we do here. I tell Stacy all the time, I never want to leave this place.”

Jolly echoed the sentiment, saying his favorite part of the job is seeing how people interact with the service and product they provide.

“It is not just about creating something,” he said. “It’s about seeing people experience something I or my team created. It’s seeing what happens when an individual on my team creates something on their own, and their face when somebody enjoys what they made. That is very, very special. That is what this job is all about.”

Braswell credits the horticulture program at Auburn for instilling in him a fire for this work.

“One of the greatest things Auburn gave me is more than my degree in horticulture,” he said. “Through the devotion of my professors, I was taught to love horticulture. They paved this path for me, and Auburn is the foundation I can always rely on.

“For Stacy and me, the goal has never been about making money,” he added. “Never. The goal is to inspire people and to provide a service to the community. Obviously, we hope to have the revenue and profit to keep the big wheel turning, so that we can continue to inspire and to leave a legacy here in this place.”

The Perfect Recipe

omewhere between sustainability and profitability lies the perfect recipe for success on every farming operation, no matter the size. In Alabama, there are three main ingredients to this recipe: the Alabama Cooperative Extension System, the Auburn University College of Agriculture and the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station (AAES).

Producers in the state look to this slate of land-grant expertise when planning for an upcoming year or making practical management decisions. Whether it is in the broiler house, pasture, orchard, field or on the catfish farm, this dynamic collaboration gives producers access to the latest and greatest production-agriculture research.

Henry Jordan is the director of variety trials for the College of Agriculture. He coordinates trials on all AAES outlying units, but said the heavy lifting is done by AAES employees at each station — including planting, maintenance and harvest. He said he has a unique opportunity to work alongside AAES and Extension professionals as they all work toward a common goal.

“It’s not a job that any of us could do alone,” Jordan said.

While changes have occurred on almost every front of production agriculture, the commitment to Alabama producers by both individuals and these institutions has only strengthened over time. Alabama Extension Director Mike Phillips said he cannot overstate the importance of the partnership between Alabama Extension, the Auburn College of Agriculture and AAES.

“Our challenge every single day is to remain relevant in subject matter content and delivery to a huge and diverse audience statewide and across so many demographics,” Philips said. “Our partnership benefits Alabama producers by staying on top of cutting-edge technology to address issues to improve profitability, production, efficiency and market opportunities — among others.”

– Paul Patterson

“These three pillars are necessarily intertwined and dependent on one another,” Patterson said. “Through the college, Auburn is preparing the next generation of farmers, agribusiness professionals — including Extension professionals — and community leaders. Faculty members in the College of Agriculture are also engaged in research and extension. Indeed, the research supported by the AAES is necessary to achieve Alabama Extension’s mission of providing researched-based information to the producers, consumers, policymakers and residents of Alabama.”

Becky Barlow, Alabama Extension’s assistant director for agriculture, forestry, wildlife and natural resources programming, said the relationship between the three entities is important because it serves as a direct link to new and exciting research happening at Auburn.

“We have specialists that are also faculty in the college,” said Barlow, who is also an associate dean in the College of Agriculture. “These individuals are conducting research and have access to university resources, as well as other non-Extension faculty who can participate in their research as part of teams.”

Phillips said one of the reasons the Extension System is successful at the county level is because producers have access to regional agents in specific, credentialled areas of expertise.

“The regional expertise is strengthened professionally through their engagement with specialists in the departments in the college,” Phillips said.

Patterson said Alabama producers benefit from the partnership in a multitude of ways.

“Alabama producers benefit from the new talent that is prepared to enter the food, agriculture and natural resource sector,” Patterson said. “Producers also benefit from the discoveries, innovations and new knowledge developed through the research process, which is then shared broadly by Extension personnel.”

Patterson said research-based Extension programs help producers make better production decisions. This enhances profits and can improve society through outcomes in situations such as improved water quality because of reduced runoff.

ne of the unique ways the three-pronged partnership benefits Alabama producers is through direct communication of research findings, according to Barlow.

“Agents and specialists have connections to producers, which allows them to get immediate feedback on processes and results,” she said. “Access to on-farm trial locations that are at a production scale allows producers to participate in processes and see results firsthand.”

A 15-year partnership between Alabama Extension Peanut Specialist Kris Balkcom and Dallas County peanut farmer Randall Beers is a testament to the effectiveness of on-farm trials, an extension of the work done at AAES outlying units.

Balkcom said one of the best things he can do as a researcher is to plant trials across the state. While Balkcom plants peanut trials at experiment stations, on-farm trials allow him and others to get a better understanding of what works best in different soil types.

Beers said it is important for him to work with Alabama Extension and Auburn researchers to determine which varieties are best suited to his environment.

“I appreciate what Extension does to allow us this opportunity,” Beers said. “New varieties are available every year. You may hear that one variety is really exceptional, but our soil types and growing conditions are all different. Until you have the opportunity to look at the varieties on your farm and in your field, you may not know what will work best for your operation.”

Jordan said a lot of effort goes into research on experiment stations that those outside may not see. While Jordan oversees and manages the results of 110 variety trials and more than 9,300 research plots, he knows without a team effort he wouldn’t be successful. He works with Extension specialists and researchers that conduct research at most outlying units.

“Without the daily support of experiment station staff, we would quite literally be out of business,” Jordan said. “I have an opportunity to work with everybody on every level as the trials happen throughout the year. Then, I work to help them compile data and share it with producers across the state. Knowing that what we do makes a difference on their operation and with their bottom line makes what we do every day worthwhile.”

Chris Parker, associate director of the Wiregrass Research and Extension Center, said the center location in Headland, Alabama, allows interested farmers and community members to stop by. Parker was a technician at the station for 15 years and said he had the privilege of learning from excellent leadership before him.

“I’ve learned that our job here is to engage every person who shows an interest in what we’ve got going on,” Parker said. “Whether they are a large-scale row crop producer or someone whose primary agricultural experience is eating three meals a day, we try to make sure we are meeting the needs of everyone who happens to come by.”

Parker said there was a period where visits to the experiment stations dwindled because of the availability of electronic communication methods.

“With the onset of COVID-19, it was a struggle to keep in contact with those we serve,” Parker said. “It was eye-opening for all of us to see that you cannot replace standing out in a test plot or cattle pen. Human interaction is important, especially when it comes to learning things that are essential for a producer.”

Since that time, Parker leaned into their station’s perfect placement and began working to involve the community with happenings at the Wiregrass Research and Extension Center.

“I am doing my best to find groups that are not interacting with us and extending an invitation to bring them here,” Parker said. “We have an opportunity to be as important to this community as schools and churches. We want to be a place that they lean on for agricultural expertise, and we are doing everything we can to be that hub.”

common theme when talking to personnel from each organization is the emphasis on the team — including everyone who researches, crunches numbers, teaches and demonstrates on behalf of a group that has Alabama’s producers at heart.

Parker said the impacts of work carried out by Auburn and Alabama Extension researchers are far-reaching.

“We can measure impacts with dollar signs, but we also care deeply about impacts through teaching experiences, conversations and station visits,” Parker said. “We are all here to help local producers and communities. Finding ways to connect with them and change their lives for the better is so important.”

Barlow said the involvement of communities and producers in university and Extension work is vital to the future of their research.

“We must continue to keep producers involved in the processes of research and exploration,” Barlow said. “They are the reason we do what we do.”

Patterson said the leadership of Alabama Extension, the College of Agriculture and AAES remains committed to collaborative work that benefits all stakeholders.

“As production, economic and environmental shifts challenge us all, new solutions, talent and knowledge will be needed,” Patterson said. “This is the responsibility of Auburn University’s agriculture programs. As these challenges evolve, teaching, research and extension will evolve to best meet these challenges.”

Phillips said he is proud of what the system accomplishes in meeting the needs of Alabama’s clientele.

“We have devoted employees who are passionate about helping to make life in Alabama better,” Phillips said. “The relationship Alabama Extension has with the College of Agriculture and the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station is special.”

Up Close & Somewhat Personal

An informal Q&A with

Morgan Martin

Many Missions

Agriculture

Program Brings

Temple Grandin

Autistic herself, she is widely seen as the rock star of the autism awareness movement, having opened eyes about what it is like to live with the condition and inspired countless numbers of those who, like her, are dealing with it. The challenges she has overcome in her lifetime, from dealing with autism at a time when it was widely misunderstood to being a rare woman in the then-man’s world of the livestock and beef production industry, have made her something of a reluctant superstar and even the subject of a 2010 HBO movie.

But to limit Grandin to only one mission doesn’t do her or her unique mind justice. She is a woman on multiple missions. And on her recent visit to Auburn as a guest of the AU College of Agriculture’s Women in Agriculture program, she was a passionate advocate for all of them.

“I always want to know what I can learn,” she told audiences in several Auburn classes and at a luncheon in her honor during a February 26 visit to campus. “If you think you’ve learned it all then you stagnate. As I’ve gotten older, I want the things I do to impact something real — to make something better. I want to open doors for other people now. I figure that is what I should be doing.”

Now 76, what she is currently doing and what brought her to Auburn is seeking to inspire the students she travels the country to speak to with the same missionary zeal she feels to solve the problems occupying her thoughts every day. Food insecurity. Agricultural sustainability. Education reform. Biofuel production. Her mind is a kaleidoscope of challenges needing solutions, so many that even she can’t get to them all. So she seeks to inspire others to take up the challenge.

Solving problems and opening doors for others has been a thread throughout Grandin’s long career whether for animals, for whom she has designed more humane facilities; other people with autism, who she has urged to never limit their ambitions despite their challenges; or students, many of whom she has helped to follow in her notably large academic footsteps. In fact, “Open Doors” is the title of a new documentary about her life, which was previewed during her visit to campus.

To watch Grandin interact with audiences is to get a glimpse of a mind that takes the old Apple Computer advertising slogan “Think Different” to a whole new level. It’s quickly obvious she is a multitasking machine — wondering simultaneously about things as varied as how the locking mechanism on the door of the airplane she flew to Atlanta that morning works to how grazing animals can actually improve their environment.

She would likely shrug at the thought, but to watch her process so many thoughts at the same time is to get a tiny glimpse of genius, albeit a genius unlike those that most readily come to mind. “I was in my thirties before I realized most other people don’t think in pictures like I do,” she related, with still a hint of that initial surprise in her voice. “I am a visual thinker. When I think of an idea, it is in pictures from my past experience that relate to that concept.”

“These young students are tomorrow’s leaders and problem solvers,” she said. “I want to inspire them. I tell them they can’t solve every problem. They need to pick one area they feel a particular passion for and are good at and concentrate on it.”

To the secondary educators in the luncheon audience, she had another message on a similar theme. As a visual thinker, she is fascinated with the “how” of “how things work” and a passionate advocate of bringing skills training back to schools so more students — especially visual thinkers like herself — can discover talents that may lie in the practical realm rather than the academic. In fact, it is the major theme of her latest book, “Visual Thinking: The Hidden Gifts of People Who Think in Pictures, Patterns and Abstractions.”

“What inspired me to write “Visual Thinking” was when I realized the skills we as a nation are losing,” she said, urging educators to rethink their curriculums. “We are paying a gigantic price for taking out all the technical, or hands-on classes from our schools. I get that parents of most kids don’t want their children taking the hands-on classes. They want them to be doctors and lawyers and stuff like that.

“Time after time,” she concluded, “I have seen similar examples. And it goes back to the educational system. In Europe, students can choose to go to university or go into tech, and they don’t stick their nose up at tech and think of it as some lesser form of thinking. I can tell you it’s not. It is a different kind of thinking. It’s the kind of thinking you need to keep the water systems running.”

And very few people have more understanding of thinking differently than Temple Grandin, whose latest and greatest mission is to inspire the next generation of students and educators — as well as children and adults dealing with autism — to take up the work of solving problems, both their own as well as those of the nation and world. It is a task she herself has spent a more than 50-year career pursuing.

“I’m in my 70s now, and there’s still so much to do,” she noted, ticking off one problem after another that she regularly pictures in her thoughts. “I’m getting older, but I want to continue to travel and encourage students like these here at Auburn to take up those challenges in the years ahead as long as I can. They are the ones that will solve them one day.”

the ant expert

By Kristen Bowman

I’m watching the seventh episode of Planet Earth III, featuring the animal on Earth with which I am most familiar.

Humans.

“Eight billion people now live on this planet,” Attenborough tells me. “And we are changing the world around us at such speed that, for animals, the challenge is to keep up.”

The episode details how animals have adapted to life with humans. It shows a rhino walking through the busy streets of Sauraha, Nepal, passing the “Rhino Lodge & Hotel” and being filmed by fearless onlookers with camera phones in hand. I watch a long-tailed macaque in Bali eat from a can of Pringles it took from a tourist at the Uluwatu temple. Then, Attenborough takes me to the far-more familiar New York City, where he starts to tell me about ants.

“The segment focuses on my research on ants in New York City,” Penick said. “Ants are small and often don’t get much attention, so I was thrilled when the BBC reached out to help them develop a pitch and serve as a scientific advisor.”

Penick worked with the production team for nearly three years as a paid consultant, and he’s studied these particular urban ants for more than seven years.

“I use New York City as a model to study how urbanization impacts biodiversity, specifically insects,” he said. “New York City is the largest and most densely populated urban area in the United States, and it has a surprising abundance and diversity of ants — there are 2,000 ants for every human living in New York City, and more than 40 ant species can be found within a 10-mile radius of the Empire State Building.”

The episode discussed what are known as pavement ants — a species thought to have arrived with the first European settlers and nicknamed so because they live almost exclusively in towns and cities.

According to Penick, insects play a dominant role in urban ecosystems in terms of both their abundance and diversity, but their role in these ecosystems remains poorly understood. The diversity of insects in cities is barely characterized, let alone the impacts of insects on nutrient cycling, soil health, pollination, disease transmission and other ecosystem processes.

Working in places like New York City, scientists like Penick study the role human foods play in urban food webs and how social insects are adapted to urban life. He’s shown that the most abundant ants in cities are those that exploit human foods.

“The research featured in Planet Earth III focuses on how ants living in the city are able to find and recruit to the foods we drop on the ground,” Penick said. “It also shows the battles ants must fight with competitors, like pigeons, as they try to secure this limited resource.”

Most ants have smooth “skin” — not really skin at all but what is known as the cuticle coating their bodies. However, some ants have elaborate textures and patterns.

Since ants emerged between 160 million and 140 million years ago, records indicate that facial textures have cycled in and out of existence. This led Penick and his former grad student John Paul Hellenbrand (now at the City University of New York) to wonder if the textures on the faces of ants might have evolved purposefully, and their work was published in Science News in January 2024.

Soil-dwelling ants have “almost psychedelic” swirling facial ridges, which could protect them from scratches in sandy soil, Penick said. The ridges are too tight for even a grain of sand to fit between.

But the idea needs further study, according to Penick and colleagues in the field. Some patterns might bolster structural support, influence biofilm growth or function in ant communication, he said. For now, we don’t know.

For the time being, we can thank researchers like Penick for teaching us — through the calming voice of Attenborough — how these foes of suburban yards are carving a place for themselves in cities around the world.

Efficient Applications

hile drones were initially used in agriculture primarily for collecting crop and field-condition data, Auburn University researcher Steve Li is leading an effort to explore how the small, remotely piloted aircraft can be used to apply pesticides and other farm chemicals.

The practice already is being used in other parts of the world, accounting for about 30% of the agricultural spraying in South Korea. In addition, 40% of Japan’s rice crop is sprayed using drones. According to the Association for Uncrewed Vehicle Systems International, a nonprofit trade group, agriculture could soon account for 80% of the global commercial drone market.

Drone spraying may be in its infancy in the U.S., but Li sees potential for its use here.

“We began working with drones and precision technologies about three years ago,” said Li, who is an associate professor in the Auburn University College of Agriculture’s Department of Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences and a weed specialist with the Alabama Cooperative Extension System. He is also a researcher with the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station.

Li and his team of graduate students now focus on using drones to deliver crop protection chemicals like herbicides, fungicides, insecticides and other chemicals used in farming operations.

“We evaluate the application efficacy of spray drones versus conventional application methods such as airplanes and ground sprayers,” Li said. “We optimize flight and spray parameters of spray drones, and we quantify and mitigate spray drift and balance coverage versus drift.”

The researchers also use drones to identify weed infestations on the ground and then deploy spray drones to spray infested spots precisely to save on herbicide costs and reduce environmental impacts.

– STeve Li

There are multiple benefits to spraying agricultural fields with a drone, he said.

“Drones allow us to spray a crop when the field is too wet after rains, they can spray small, odd shaped fields better than airplanes and ground sprayers, they handle hilly terrain and terraces very well, and they use much less fuel than ground sprayers and airplanes,” Li said.

Other benefits to drone spraying, he said, is their ease of use—they do not require prior aviation knowledge with fixed wing airplanes or helicopters. Also, they do not cause physical damage to the crop and do not cause soil compaction or create gullies when the soil is wet.

“Drones are much less expensive than ground sprayers and airplanes, the maintenance required is low, they are simple to repair and change parts without special training and knowledge, and it is easy to transport drones on highways, roads and over long distances.”

Drones can be beneficial on both large-scale and smaller farms, Li said, but they may have a niche on small farmers due to the economics involved. Spray drones cost only a fraction of large self-propelled ground sprayers.

While the benefits are numerous, Li’s research also has revealed some limitations to using drones for agricultural spraying.

“Battery life and tank size are still less than ideal and midair collision is always a concern,” he said. “Other disadvantages at the present time include signal loss, forced landings, overheating and equipment depreciation because they are considered electronics.”

The flagship models of drone agricultural sprayers can cost from $35,000 to $55,000. Thanks to Li and his partnership with Agri Spray Drones, Auburn University was the first land-grant institution in the United States to use the new DJI Agras T40 spray drone in agricultural research.

Li sees hardware limitations and FAA regulations as the two biggest hurdles for farmers hoping to convert from conventional to drone spraying.

“The end goal is not to replace current application methods but to find a reasonable and complementary way to work spray drones into the field management equation.”

As with commercial pesticide applications, Li advises growers to always follow product labels and obtain required licenses from the FAA and state departments of agriculture when applying materials with a drone.

Li has received multiple grants for his drone research, including commodity grants from Alabama Farmers Federation check-off dollars, the National Peanut Board and the crop protection industry. He recently received the Rittenour Award for Production Agriculture & Forestry Research presented by the Alabama Farmers Federation. The award recognizes Auburn faculty for creative research. He received $10,000 from the Alabama Farmers Agriculture Foundation to continue his drone presentations and on-farm research that has helped farmers across commodities harness innovative technology for crop protection.

Strawberry Shortcake

The Monterey, Virginia, native started cooking as a child. The fourth child of six, her experience in the kitchen began with birthday cakes.

“As soon as we could see over the counter, we could help make our birthday cakes,” she said. “At some point, our dad kept asking for baked goods after teaching us how to make them, and it grew from there.”

Adams is at home in a kitchen. While she likes cooking all kinds of things, she has a special place in her heart for baking. This tried-and-true strawberry shortcake recipe is a favorite of hers, which she baked and photographed on her dad’s worktop in Virginia.

Tried-and-True Strawberry Shortcake

Tried-and-True Strawberry Shortcake

Ingredients

For the strawberry topping

- 4 cups strawberries

- 1/4 cup sugar

- Pinch of salt

- 3/4 cup strawberry jam

- 1 tablespoon of lemon juice

For the shortcake

- 3 cups all-purpose flour, spooned and leveled

- 1/3 cup granulated sugar

- 1 tsp. Salt

- 2 tbsp. baking powder

- 3/4 cup butter, cold and cubed into small chunks

- 1 large egg, cold and whisked lightly

- 3/4 cup buttermilk, cold

- 1-2 tablespoons cold buttermilk or ice water

For the whipped cream

- 2 cups heavy cream

- 1/3 cup powdered sugar

- 2 teaspoons vanilla

tips & Tricks

Instructions

For the strawberry topping

- Chop the strawberries into the desired-sized pieces and toss with sugar and salt in a bowl. Let it sit for about 30 minutes to draw the strawberry juice out.

-

Heat the jam over medium heat for 3-5 minutes until no longer foamy. Add to the strawberries along with the lemon juice and stir together.

Note: This topping should be served at room temperature or chilled, so it’s best to do this before you start on the shortcakes.

For the shortcake

- Combine flour, sugar, salt and baking powder.

- Cut the butter into the flour mixture using a pastry cutter. Cut until it’s a crumbly mixture with pea sized pieces.

- Add the buttermilk and egg to the mixture and combine gently until you have a shaggy dough. The flour may not be all mixed in, and that’s okay.

- Knead by hand until the dough comes together. If it’s too dry to combine, add a tablespoon of extra buttermilk or ice water until it does.

- Turn the dough onto a flour surface and roll in a 9×13 rectangle. Fold the dough in half, then into quarters, and once again for a total of three turns. If it’s too tall, gently roll until it’s about 1 ¼ inches thick.

- Using a 2 ½ inch biscuit cutter or a tall glass, dip into flour and cut the dough. Press straight down and do not twist. Re-roll the scraps and repeat.

- Place into a buttered 9X9 square baking pan. Having a pan with taller sides helps to prevent them from falling over. They should be snug in the pan or about ½ inch apart depending on how many you get.

- If time allows, freeze for 20 minutes while the oven is preheating at 425 F. This helps to keep flaky layers in the shortcake.

- Once the oven is preheated, brush the tops with heavy cream and sprinkle with sugar and then bake for 18-22 minutes until golden brown.

For the whipped cream

- Mix all three ingredients until you get stiff peaks and keep refrigerated until ready to serve.